Green Climate Fund commits billions, but falls short on disbursements

This year, the United Nations Green Climate Fund will commit over half of its $8.3 billion budget for climate change adaptation and mitigation initiatives, including a milestone $1 billion approved at its last board meeting in February.

This development comes as the fund continues to struggle with actually disbursing the money it has committed while preparing for a critical year ahead, with the rule book of the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change expected to be finalized by December.

When the rule book is set, developing countries will ramp up their need for outside financial and technological support in order to maximize their individual targets to reduce emissions. Developing countries set the targets themselves, based on each one’s ambition and capability to reduce emissions domestically.

They are expected to be enhanced over time and are at the core of the agreement’s long-term goal to keep global warming well below 2 degrees Celsius.

With GCF designated as one of the operating entities of the financial mechanism of the agreement, not to mention the world’s largest international climate fund, the pressure is higher than ever for it to churn out even better results.

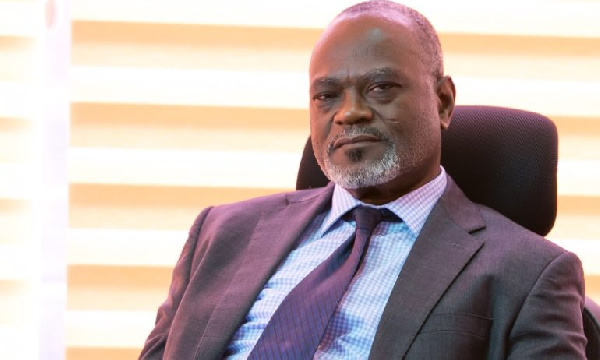

But Kilaparti Ramakrishna is not phased. The director ad interim of external affairs at GCF tells Devex that he’s confident that the fund can meet developing countries' needs, especially under the guidance of its new co-chairs, Paul Oquist of the Republic of Nicaragua, and Lennart Båge of Sweden, both of whom were appointed last February.

"They both have immense knowledge not only on climate negotiations, but I was pleased to see, [on] a lot of the climate science and the impacts to ensure that the GCF is able to play its part,” said Ramakrishna.

While it's too early to tell how the co-chairs will move forward, civil society organizations are already noticing a difference and are praising their leadership style.

“The co-chairs provide a very steady, calm presence,” Liane Schalatek, the associate director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation North America, one of two civil society organizations that are active observers present at GCF’s last board meeting, tells Devex.

The comment is a stark improvement from the at times tenser relations between CSOs and the fund’s board members, which culminated during a board meeting last July.

At the event, CSO representatives were repeatedly denied the opportunity to air their grievances about GCF’s continued accreditation of banks and development agencies with a long history of funding fossil fuel projects, among other things. Outraged, groups, such as Friends of the Earth, the Asian People’s Movement on Debt and Development and ActionAid held protests outside GCF’s headquarters in Songdo, South Korea.

Schalatek, who also picketed, says that CSOs will continue to disagree with certain policies and fund decisions. But, she commends the co-chairs for demonstrating a willingness to consult with them more proactively on contentious issues, such as the approval of project proposals.

On February 26, the first day of the last board meeting, active observers were able — for the first time — to share written comments on all 23 proposals before board deliberations started directly with the co-chairs and secretariat.

The secretariat then responded to some of the concerns directly and publicly during the board meeting. Schalatek found it “interesting” to get their input in response to CSO recommendations that certain proposals shouldn’t move forward. “Afterwards, some of the accredited entities also got in touch with the CSOs and provided commentaries," she adds. “That was very, very helpful.”

Ultimately, all 23 proposals amounting to over $1 billion were approved at the meeting, demonstrating the fund's ability to ramp up operations. But the type of projects that are being approved remain largely underwhelming, argue CSOs, especially in light of the GCF's mandate to promote “transformational change.”

For instance, the board approved more than $86 million for a project in Vietnam designed to scale up energy efficiency for industrial companies. In a rare moment, both the CSO and private sector active observers in interventions made in the boardroom agreed that it wasn't the right project in the right environment — though it was ultimately approved.

Other approved projects had questionable approaches. For example, CSOs were concerned that a project in Bangladesh, which is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to create a global clean cooking program, was arguably more focused on supporting the distributors of cooked stoves rather than ensuring that poor people would be able to afford the improved stoves in the first place. Nor did they sufficiently factor in gender dimensions, which is critical considering that women generally make the everyday buying decisions for the household. “Wouldn't you have to not just look at the supply side, but also the demand side?” questions Schalatek. And yet the board approved $20 million for the project.

But approving funds is not the most challenging issue facing GCF — it is disbursing them. As of December 2017, the fund has only released roughly $150 million, or less than 6 percent of the nearly $3 billion it had committed up to that point. “The disbursal is terrible,” says Indrajit Bose, a senior research officer at the Malaysia-based nonprofit, Third World Network. “It really needs to be stepped up.”

What is taking so long has mostly to do with the legal documentation requirements and various conditions that are imposed on projects when they get approved? For instance, two documents, the accreditation master agreement and the funded activity agreement, need to be signed before any money is disbursed. But, some of the accredited entities putting forward project proposals have been taking an extremely long time to come to a negotiated agreement with GCF on the necessary paperwork guiding their relationship.

It took the World Bank more than a year to sign their accreditation master agreement, during which time some of their project proposals worth tens of millions of dollars were already approved, but unable to actually be implemented.

GCF’s Ramakrishna says that this critical issue engages his colleagues on an almost daily basis, both in terms of refining their approaches to disbursement and putting the needed amount of pressure on key stakeholders.

“We have a very ambitious target of $900 million disbursement by the end of the year and that is a very steep curve for us,” explains Ramakrishna. “There's only so much we can do. There are timelines for the grant itself and the activities of accredited entities and the activities of the national governments. We are pushing as hard as we can and we hope to reach that level.”

Adopting new policiesGCF is still relatively new. Having become fully operational only three years ago, it has struggled with a host of growing pains ranging from staffing shortages to criticisms of its accreditation process. But the fund has taken significant steps to enhance its overall capacity, most recently by adopting the Indigenous Peoples Policy as well as an environmental and social policy.

"A significant number of projects that have been approved by the GCF are going to be implemented in indigenous people territories," Helen Magata, communications officer at Tebtebba, a Philippine-based international nonprofit focused on indigenous people's rights and the alternative CSO active observer at the last board meeting, tells Devex.

"We wanted to make sure that the GCF recognizes that IPs are not only victims, but active agents of climate action.”

The policy, which was developed after conducting consultations and gathering input from a wide range of indigenous people's organizations, including Tebtebba, has three key features: First is to ensure that the fund not only aims to avoid harm, but just as importantly, “do good for IPs” who have a very intimate relationship with their land and thus have developed unique systems and processes to adapt and mitigate to climate impacts.

Second is to recognize the need to develop guidelines on how to obtain free prior and informed consent of IPs who are potentially affected by a proposed project before it can be approved. And last is to ensure that IPs are engaged at all levels of the projects, activities, and programs of GCF to secure their rights.

At the moment, IPs, who are widely considered to be some of the communities most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, have yet to put forward their own project proposal. Given their limited resources and the stringent demands of GCF, Magata says IPs feel that it’s best to partner with an accredited entity and are currently scoping out potential candidates.

Although GCF has to date overwhelmingly approved projects from multilateral institutes, there is increasing rhetoric about country ownership at climate funds, and IPs would ideally like to work with their national governments. In many parts of the world, however, IPs are at odds with their own government, who may not recognize their rights, especially over land.

“We've been vocal on this issue because the GCF is now developing its country ownership guidelines and we want to see it state that country ownership doesn't only mean government ownership,” said Magata. “There are various other actors in the country, including IPs, women, fishermen, etc.”

At the core of the IP policy is human rights, which the fund’s highly controversial interim performance standards are not nearly strong enough on. The newly approved environmental and social policy provides hope however. The policy, which Heinrich Böll’s Schalatek calls “a big step forward,” outlines the fund’s approach to the environment and the protection of the people and things living in it.

As part of the fund’s environmental and social management framework, the new policy provides guidance to the application of the fund’s environmental and social performance standards. These were adopted from the World Bank’s International Financial Corporation on an internal basis and the new policy leaves the option open for GCF to develop its own safeguards down the line.

Moving forwardDeveloping countries are already thinking about the fund’s first official replenishment process, which will be automatically triggered this year once GCF spends 60 percent of its budget.

Given that the entire process will take a total of 18 months, board members have been discussing the best path forward.

Developing countries have clearly stated that they want the process to be based on their needs, as is consistent with the Paris accord. And they are looking to the 24th annual Conference of the Parties taking place this December in Poland as an opportunity to tease out the willingness of major developed countries to financially recommit to the fund, says Heinrich Böll’s Schalatek.

Replenishment remains a highly political process and at least one developed country won’t make it easy. At the last board meeting, U.S. board member Geoffrey Okamoto echoed President Trump’s stance on the fund by stating that replenishment is not an urgent issue and that some countries might be “uncomfortable” with a needs-based approach.

There isn’t any other viable approach unfortunately. As GCF’s Ramakrishna points out: “When we say that we need funding of X number of dollars, it is based on some judgement both in terms of what can be had and also in terms of what is needed. These two cannot be independent of each other.”

Yet, ultimately the decision adopted on replenishment excludes the needs of developing countries. It is now a benign process where the co-chairs with the support of the secretariat will oversee the preparation of some necessary policies and procedures for replenishment.

Still, the needs of developing countries is not completely out of the picture yet. “These are still just the first steps,” says TWN’s Bose. “But, you can already see where the tension lies.”